Greg Snyder

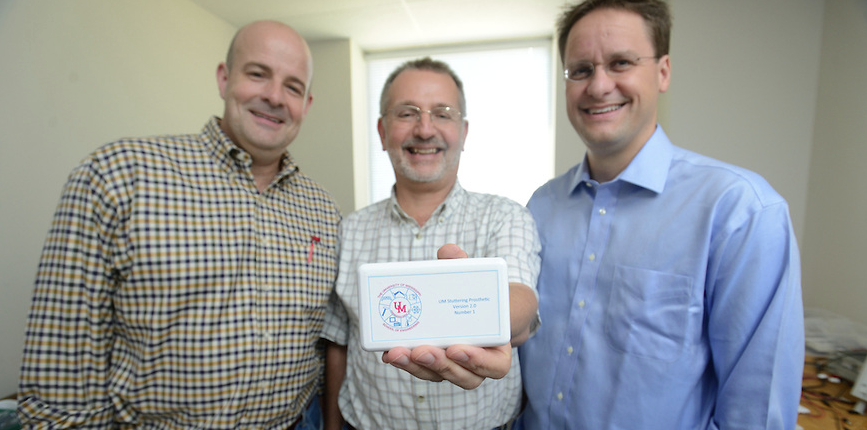

Greg Snyder knew the drawbacks of traditional stuttering treatments when he set out to determine whether a novel idea he’d had might provide an alternative. Snyder, associate professor of communication sciences and disorders, has a stutter, but he noticed a reduction in his own symptoms when he used his fingertips to feel his throat vibrate while speaking. His idea—that a tactile feedback device might be used to treat stuttering—had the potential to help people worldwide by offering a convenient, cost-effective and less intrusive stuttering prosthetic than the existing options.

Snyder decided to test his concept by enlisting the help of colleagues across the University of Mississippi campus. A casual conversation in the Grove on a brisk autumn day led to a multidisciplinary collaboration, and ultimately to the creation of a commercially licensed product.

Using sensory feedback to treat stuttering is an established idea. For years, researchers have known that auditory and visual feedback help evoke information that the speaker intends to produce thanks to what is known as “gestural initiation.” For example, stuttering is curbed when someone sings with a choir or speaks along with a church congregation. The same holds for visual feedback, such as looking at one’s reflection or using a puppet to prompt speech.

“When I speak, I stutter because I can’t get my own speech gestures started—it’s a self-initiation problem,” Snyder said. “If I say the word “stutter” and get caught on the first ‘t,’ I’m not stuttering on the ‘t’ but on the sound that comes after it. That’s the sound that’s not being initiated.”

Snyder’s breakthrough came in discovering that tactile feedback could provide similar benefits to those of audio and visual feedback—with fewer tradeoffs.

“It makes sense that if it works for auditory, or if it works for visual, then it should also work for tactile,” he said. “What I’m really doing is providing a certain sensory input that lets me bypass part of my brain with an alternate neural pathway.”

Dwight Waddell

The device also has the advantage of being less intrusive in conversation than auditory or visual devices. Visual feedback prevents the speaker from maintaining eye contact during conversation, while audio feedback devices may impede normal conversation by distracting or irritating the speaker with amplified background noise, frequency shifts or time delays.

“Speech feedback through the auditory channel is annoying,” Snyder said. “Imagine Minnie Mouse parroting your speech with a noisy amplifier.”

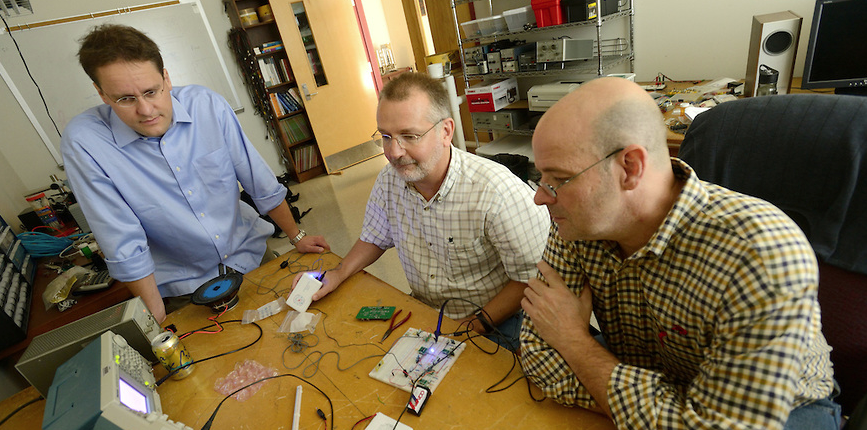

To develop a device that could mimic what he experienced by holding his hand to his throat, Snyder first enlisted the support of Dwight Waddell, an associate professor of electrical engineering and researcher who has expertise in neuroscience, neurological disorders and neural system function. Waddell quickly understood the theoretical basis of the proposed device, recognizing its potential applications, and became the driving force behind its development. Waddell turned to Paul Goggans, professor of electrical engineering, to develop a prototype.

Paul Goggans

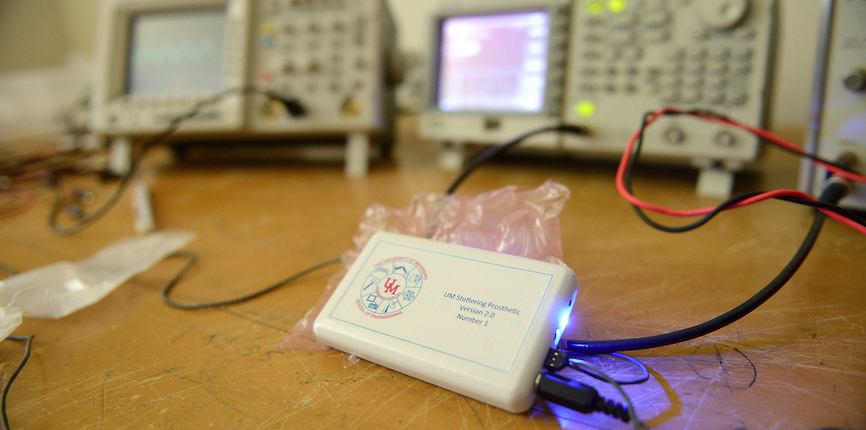

The device they developed has a sensor that rests on the speaker’s throat and communicates feedback to a “skin stimulator” that can be held discreetly in one’s hand. Theoretically, the “skin stimulator” could be placed on any part of the body sensitive to touch; possible applications could include attaching the stimulator to the inside of a watch wristband or a shirt cuff.

“Tactile information isn’t part of your normal mode of communication,” Waddell explained. “With a tactile device, you’re getting feedback with a sensory apparatus that isn’t part of your repertoire to communicate. It’s not burdening.”

The inventors stress that the device is not a cure-all. Although it helps alleviate the symptoms of stuttering, the underlying disease persists. They also stress that the device’s effectiveness depends on proper training. Otherwise, there exists a risk that users could become habituated to the device, lessening its effectiveness—a problem for many who use auditory feedback devices.

The device promises to have a significant impact on people whose lives are affected by stuttering, particularly children and adolescents who feel social pressures to conform and may feel alienated by stuttering. Underlying the stigma of stuttering is the widely held but scientifically contested view that stuttering is a behavioral problem that can be modified with enough willpower.

Walt Chambliss

“I’m working with my clinic on campus to develop a treatment that works with the device, but it doesn’t just stop there,” Snyder said. “It works with the whole person—if you add another layer of education for the public and the client and their extended family, then you’re beginning to treat the person, the condition, but also the entire ecosystem.”

A Technology Commercialization Initiative grant funded by the U.S. Small Business Administration* and issued by the UM Division of Technology Management provided the funds needed to develop a prototype of the device. The device’s patent rights were then licensed to HTG Medical Devices LLC of Tupelo.

“We’re excited to work with a local company to commercialize this technology,” said Walt Chambliss, UM director of technology management. “It’s an opportunity to make an economic impact here in the state with a University of Mississippi-developed technology.”

Allyson Best

The road from a conversation in the Grove to the development of a marketable product relied on a few key steps: a great idea, good chemistry among collaborators and the expert guidance of the UM Division of Technology Management. According to Allyson Best, associate director for technology management, the device’s success demonstrates the promise of interdisciplinary collaboration and the research-to-commercialization continuum that can drive economic development in the state.

“This is an extraordinary example of what can happen when experts from different fields are open to collaboration,” Best said. “Together they transformed an idea into a real opportunity that we hope will soon be available for these patients. This type of interdisciplinary research is an exciting part of successful innovation here at UM.”

*This project is funded by a grant from the U.S. Small Business Administration. SBA’s funding should not be construed as an endorsement of any products, opinions, or services. All SBA-funded projects are extended to the public on a nondiscriminatory basis.