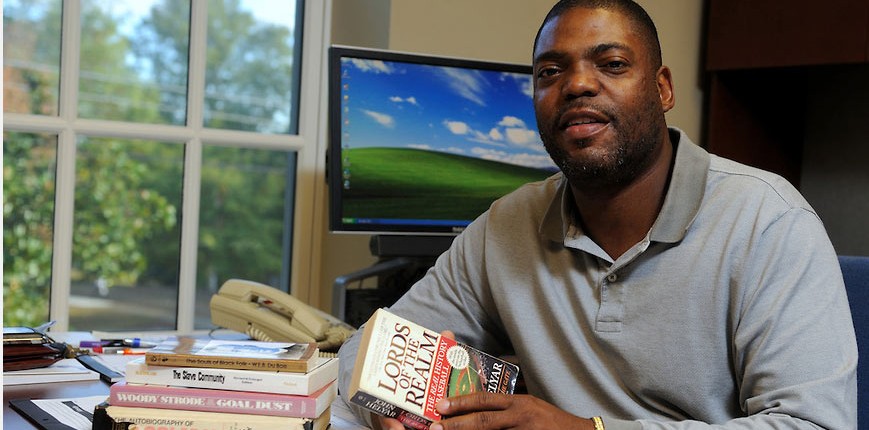

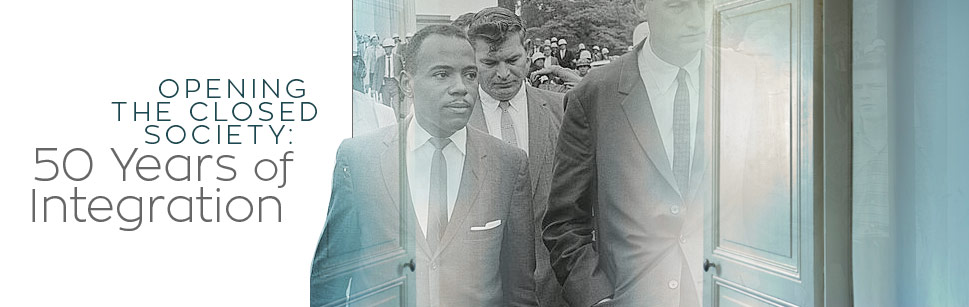

Charles Ross

For many years after the bloody riot that marked James Meredith’s arrival on campus, the legacy of 1962 seemed like a burden to be overcome.

Today, it’s a legacy Ole Miss carries with open hands, as a steward for the future.

“I think that our institution has more responsibility than any in the state for trying to lead Mississippi forward in race relations,” said Charles Ross, director of African-American Studies and associate professor of history, who chaired a campuswide effort in 2012 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the university’s integration.

“For such a long period of time, the university played a very different role,” Ross said. “It epitomized the closed society and segregation, and not allowing African-Americans to have access to higher education.

“But the institution must be given credit for realizing, over the last 20 to 30 years, that in order to not be defined by what happened in 1962, it also must not run from its past. We have to talk about how we’ve changed, what we’ve learned and how we still can grow.”

It’s a message that resonated loud and clear during the yearlong commemoration of Meredith’s enrollment as the university’s first African-American student.

Led by Ross, a committee of some 20 faculty, staff and students was assembled and funded by the office of UM Chancellor Dr. Dan Jones. The group spent nearly a year working on plans for events that would touch every corner of campus and reflect upon the legacy and lessons of 1962 from nearly every angle. Academic departments and student groups offered their contributions, too. The result was a sweeping and thorough exercise in embracing both the shame and the victory of Ole Miss’s integration story.

Don Cole

“There were a host of events, and all of them were memorable,” said Donald Cole, assistant provost and assistant to the chancellor for minority affairs. “The open environment that was created with this yearlong event did much, I think, for now and future dialogue that will allow the reconciliation and healing process to continue to take place.”

The observance kicked off with the September 2011 dedication of Silver Pond, in honor of the late former professor James W. Silver. A member of the history faculty from 1936 to 1964, Silver stirred controversy for criticizing the racial taboos of his time and left the state under pressure after his publication of Mississippi: The Closed Society in 1964.

A historical plaque near the Sorority Row entrance to campus honors him as a “defender of free speech, academic freedom and progressive values,” and a picturesque pond bears his name.

“It was very meaningful to have his family back on the campus,” Cole said.

The slate of events conducted over the year that followed included lectures and brown-bag luncheons, panels and prayer services, concerts and art exhibits.

In March 2012, a multi-session Day of Dialogue brought African-American alumni back to campus to reflect upon their time and experiences at Ole Miss. The day included a lecture by civil rights activist and author Myrlie Evers-Williams, who returned in May 2013 to deliver the campuswide commencement address.

Featured speakers over the course of the year included historian William Doyle, who authored “An American Insurrection,” a chronicle of the 1962 riot, and also assisted Meredith with his recent memoir, A Mission from God.

UM historians adding their perspectives included David Sansing, an emeritus professor and expert on Ole Miss history, and Charles Eagles, history professor and author of The Price of Defiance, an award-winning chronicle of the university’s integration story.

Other noted lecturers in the lineup included Marian Wright Edelman, an activist for the rights of children and the disadvantaged.

For the committee charged with coordinating all the various events, communication—both within the group and to the broader university community—was key to success of the observance.

“We had a website, we disseminated information to newspapers and we also had flyers for certain events,” Ross said. “We were pleased that most of the events were well-attended.”

The yearlong commemoration culminated in a special series of events around the actual 50th anniversary of Meredith’s admission to the university on Oct. 1, 1962.

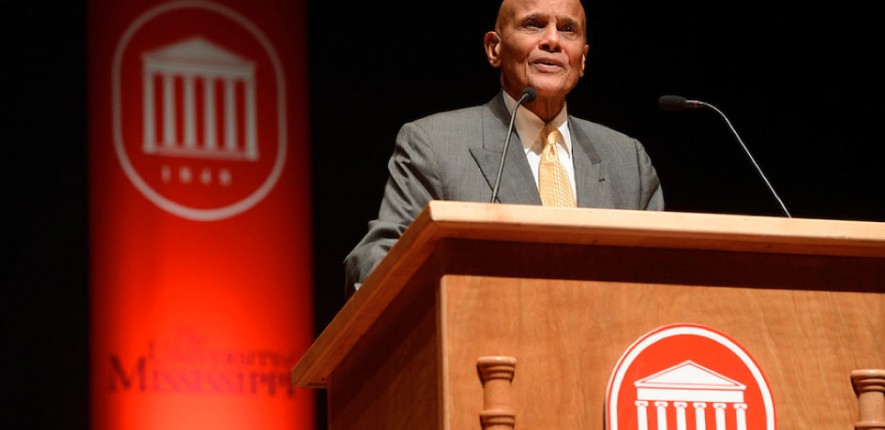

U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder was on hand to speak at the fall convocation of the UM Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. The anniversary day featured a keynote address by entertainer and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte, who recalled his first visit to Mississippi alongside friend and fellow actor Sidney Poitier during the Freedom Summer of 1964.

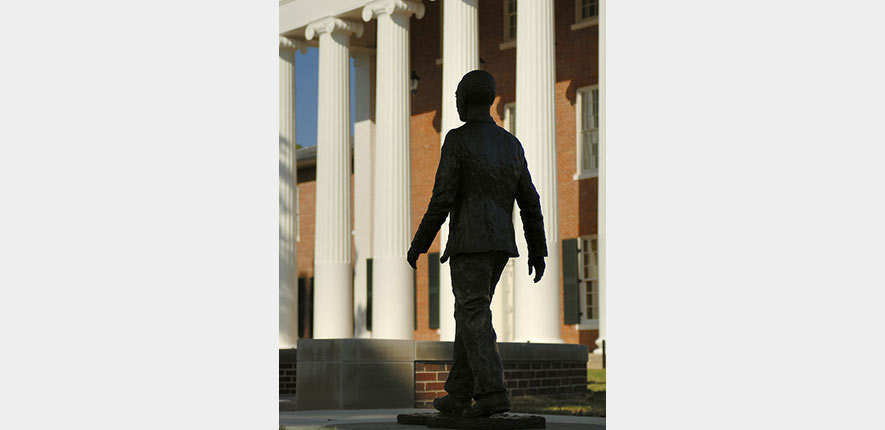

The evening of his address, Belafonte was joined by the chancellor and a flock of students for a walk that traced Meredith’s likely path from his dormitory at Baxter Hall to the Lyceum, where he won his admission to the university.

“It was a chance for the students to imagine what it felt like to walk in his footsteps,” Ross said. “Students have read about the civil rights movement or watched programs on TV, but this was an opportunity to connect the details of what happened with the places they walk by every day.”

Andy Mullins

Making such connections for today’s students—two generations removed from the civil rights era—was a critical focus of the commemoration.

Andy Mullins, former chief of staff to the chancellor and co-chair of the commemoration’s civil rights movement and civil war subcommittees, said it was important for students to gain more knowledge about the events surrounding Meredith’s admission and to grow in understanding as members of a diverse society on campus and beyond.

“Dealing with race relations is part of our legacy at the University of Mississippi, and that doesn’t end when the ceremony is over,” Mullins said. “We hope the entire observance emphasized that race relations need constant nurturing and constant work.”